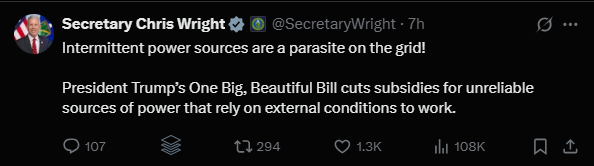

Secretary Wright described intermittent power sources as “a parasite on the grid” today.

But are they?

In biology, a parasite is defined as an organism that benefits at the expense of another.

Intermittent energy sources like wind and solar do rely on other resources—typically dispatchable and reliable ones—to balance the grid when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing.

When they are generating, they tend to displace these other assets, which must ramp up and down in response. This can create inefficiencies, underutilization, and added infrastructure costs—all of which can burden consumers.

Framed this way, the “parasite” label has a certain logic: intermittent sources gain from the grid’s reliability, but may impose costs on the very assets that provide it.

But that framing leaves something out: the possibility of mutual benefit.

Let’s borrow from biology again. Symbiosis isn’t just parasitism—it also includes:

Mutualism – where both species benefit. This might describe a solar-plus-storage project or a grid design where renewables and responsive loads complement each other.

Commensalism – where one benefits and the other is unaffected. Think of zero-marginal-cost solar power serving price-sensitive, flexible loads that don’t require backup.

Intermittent resources do have valuable attributes: their levelized cost of energy (LCOE) - acknowledging the flaws of this metric - can be among the lowest available. Their marginal cost is effectively zero. Those attributes can have a positive impact when integrated effectively.

The label “parasite” assumes a grid context where:

Loads are inflexible

Backup resources aren’t compensated fairly

Infrastructure is static

But that context isn’t fixed or uniform. It is possible to imagine (even if it is not your prediction) a future (and/or specific locations) with abundant storage (perhaps via EVs), smart grids, and flexible demand where the relationship is far from parasitic.