Phase I of the AESO’s Large Load Integration Program is complete, and the full 1,200 MW has been allocated.

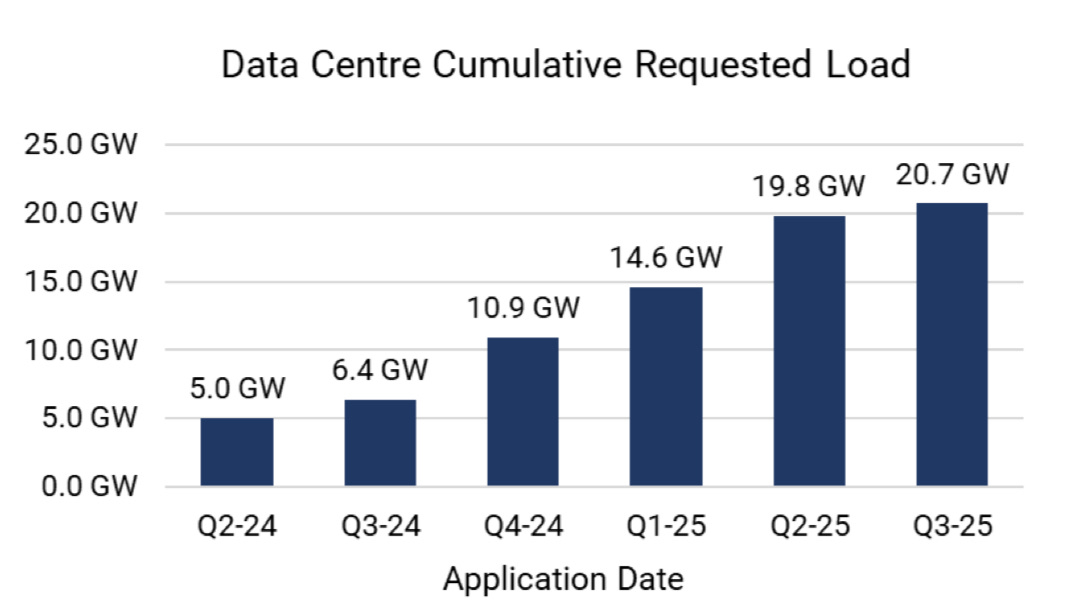

The outcome highlights both the scale of the opportunity and the structural constraints facing data-center development in Alberta. With 20.7 GW of load-service requests in the September Data Center Update, the allocation result should surprise no one: any market with gigawatt-scale headroom will attract a surge of proposals.

Despite dozens of applicants, the 1,200 MW in Phase I ultimately went to just two projects:

970 MW to P2936 GLDC Load (Pembina + Kineticor)

230 MW to P3083 Keephills Data Centre Phase I (TransAlta)

Why only two?

Phase I imposed stringent “shovel-ready” requirements: completed engineering studies, land control secured, financial security posted, and the ability to connect without major transmission upgrades—all within the interim 1,200 MW cap.

When these filters were applied, only GLDC and Keephills met the bar. Both had also requested materially larger allocations (~1,800 MW and ~395 MW respectively). The design worked as intended: advance a meaningful volume of credible, near-term load while staying within existing grid capability and regulatory limits.

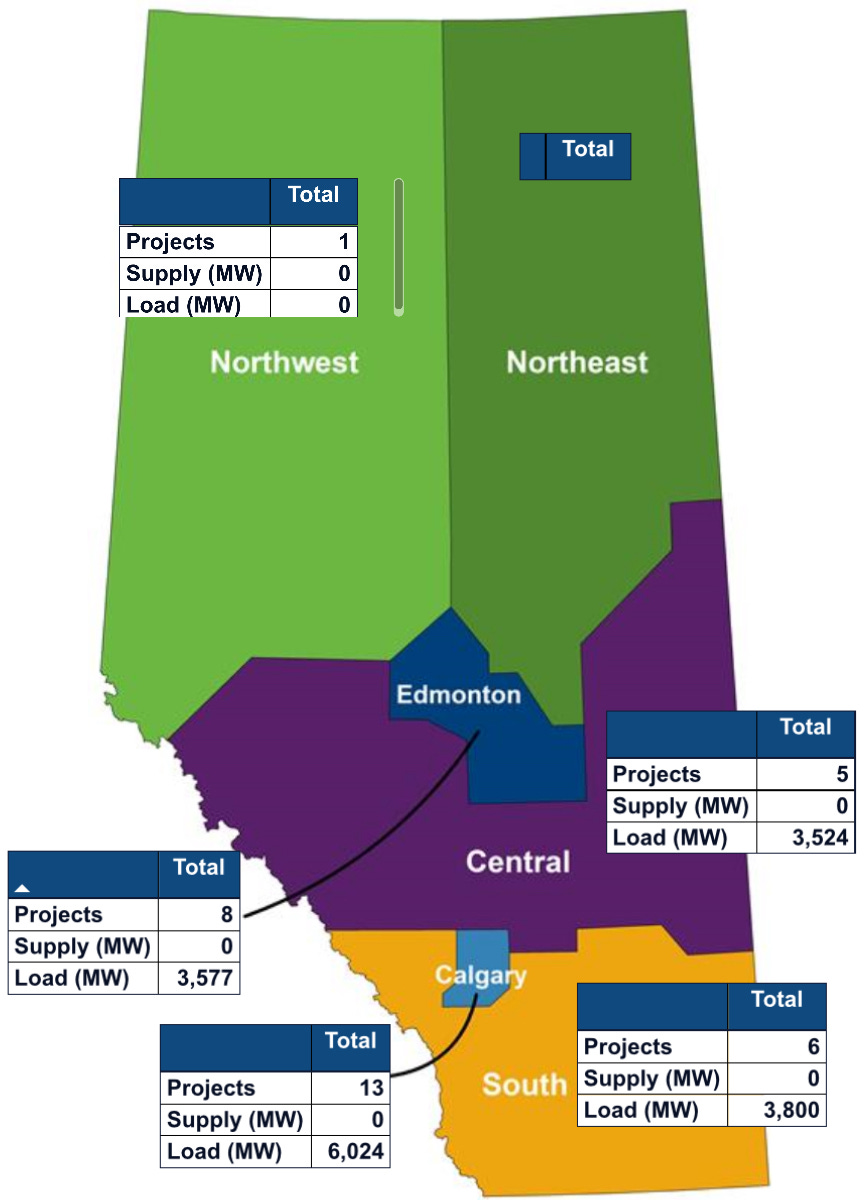

The remaining ~17.9 GW of projects (19.1 GW in total requests) now fall to Phase II, which must confront a set of harder, structural questions that Alberta shares with every jurisdiction experiencing rapid data-center growth:

Beneath these questions lies a fundamental issue: Alberta’s difficulty in adding new dispatchable capacity, without which large-scale data center growth becomes constrained. Key hurdles include:

Policy and carbon uncertainty: CER post-2035 rules and rising carbon prices cloud long-term economics unless CCS is added.

Energy-only market risk: No capacity payments or guaranteed offtake; investors rely solely on spot prices to recover capital.

Timeline mismatch: Dispatchable plants require 5–7 years to build; data centers materialize in 18–36 months.

Transmission and siting constraints: Existing corridors are congested; upgrades are costly and slow.

Financing difficulty: Large thermal builds lack long-term contracts or policy stability needed to de-risk investment.

Given those obstacles, how did Alberta still have 1,200 MW, plus the associated transmission flexibility, to allocate in Phase I? A combination of timing and structural legacy factors:

Coal-to-gas transition (2019–2023) retired ~6 GW of coal and added even more gas and renewables, increasing net headroom.

Flat demand for over a decade meant supply growth outpaced load.

Transmission infrastructure built for the coal fleet remained in place, creating underutilized but available corridor capacity.

Key question going forward: How much additional capacity can Alberta unlock, how quickly, and what share of today’s 19.1 GW of proposed load will ultimately convert into real, interconnected demand?

This will define the trajectory of Alberta’s data center sector, and the grid that must support it.